An Intro to Information Management

In order to meet their information management needs, many organizations develop formalized Information Management Systems (IMS). The complexity of a particular Information Management System lies in the complexity of the information involved, and the complexity of the organization and its operation. The field of information management is the study of these IM solutions, what makes some better than others, and how to improve them.

In this blog post, we’ll briefly introduce the primary domains of information management, and the goals that organizations should have for each when developing their own Information Management System.

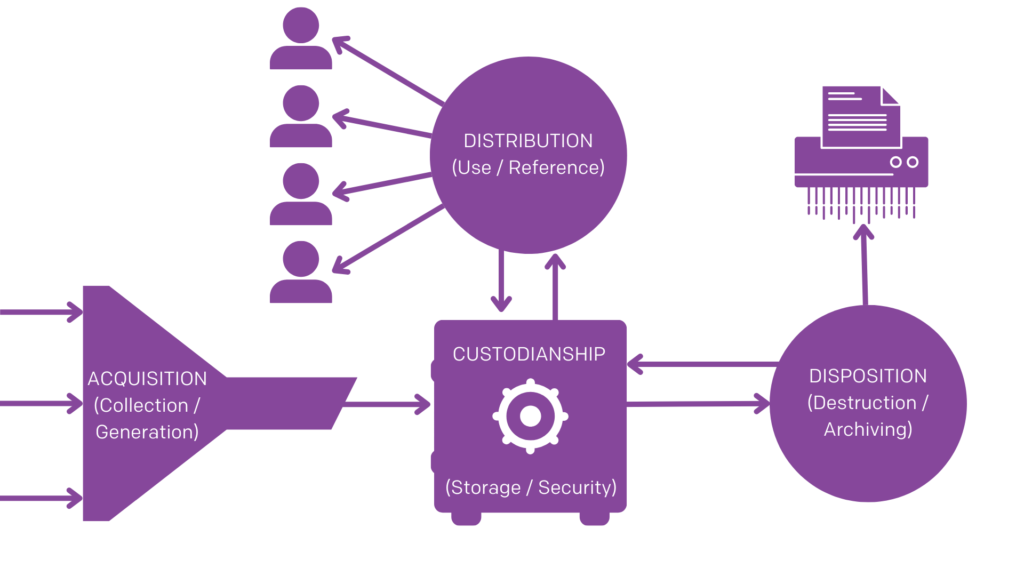

The Four Domains of IM

Acquisition

Goals: Accessibility, Efficiency, Organization

“Acquisition” is how you generate, collect, or receive information. For example, an invoice from a service provider you’ve hired would be received via physical or electronic delivery (i.e. paper mail vs email), whereas an SOP manual written by your employee is “acquired” in the sense that it has been generated internally.

For most organizations, excellent information acquisition is as simple as making it easy for people to send you information in a variety of commonly used formats. It should be as easy as possible for partners, customers, or clients to send you information or documents when they need to.

However, if your organization’s business model is centered on information, excellent acquisition may actually be enormously important and complex. A social media company, for example, wants to collect as much information about their platforms’ users as possible, in order to maximize the effectiveness of their targeted advertising. A research and development firm, on the other hand, would want to be able to quickly and systematically interpret and incorporate complex information.

The end of the acquisition stage blends into the custodianship stage, as files which are “acquired” need to be stored somewhere. Good acquisition is not just about the volume or quality of the information collected, or the ease with which it is received, but also about where that information ends up in your storage.

Custodianship

Goals: Organization, Security

This is a broad term covering how the information is stored, including how it’s organized and how it’s protected. Generally, good custodianship involves effective, intuitive organization and strong, comprehensive security. So a loose pile of all your paper invoices jammed into a safe is not good custodianship, but neither is a well organized but totally unsecured online folder.

An important part of custodianship for any organization with a large number of files is using an effective and logical indexing schema; in other words: how are your files and folders organized, and why? One way to think of an indexing schema is a list of types of information about a file (i.e. metadata) arranged from most broad to most specific, and/or from most important to least important.

An example of an indexing schema might be “Department> Year> Project> Purpose> Type> Format> Date Created.” With this schema files are sorted by department, then within department by the year they were created, then within that year by the project they’re relevant to, and so on.

Creating the best indexing schema for your organization will mean considering the operational context, the extent of your storage needs, and the organization tools at your disposal, among other factors. Whatever your schema ends up being, though, it needs to be applied consistently to all of your storage. That way, it can be learned once, and used to effectively navigate to any file in any collection.

Distribution

Goals: Accessibility, Efficiency, Security

Distribution overlaps with custodianship quite a lot, as it involves how information, and access to information, are distributed throughout your organization. A well organized collection is easier to distribute and access. Part of secure and effective custodianship of information is ensuring that sensitive information is properly distributed only to those with permission to access it. So, for example, good distribution of your invoices would involve making them easily available to your accountants, and not to employees that don’t need access to them.

There’s two ways to think about distribution: passive and active. Passive distribution of information is the distribution of access to information, such as who in your organization has access to which file storage locations. Active distribution involves sending information to members of your organization, rather than just making it accessible to them.

So after you’ve received an invoice, for example, and you’ve stored it somewhere organized and secure, you could either leave it stored in a specific folder for your accountants to access at their leisure, or send it directly to their accounts. Whether to choose active or passive distribution for any particular piece of information will depend on the operational context and your team members’ preferences; one is not inherently better than the other absent those considerations.

Disposal

Goal: Compliance, Security, Diligence

Disposal is exactly what it sounds like: what you do with your information when it’s no longer of use to you. Excellent information disposal involves good information security, compliance with legislation, and diligence.

Compliance.

Every step in good information management involves understanding and complying with the relevant legislations about records management, and this is probably most true of the disposal stage. Most jurisdictions require organizations to hold onto important records for a number of years after they’re created, even if they’re no longer relevant. These rules exist to keep organizations accountable, as even records which are a few years old can be used to assess the compliance or non-compliance of an organization’s practices.

Understanding how records retention and disposal legislation apply to your operation is crucially important, as disposing of a record before it’s legally allowable could be seen as an attempt to hide evidence of illegal activity, regardless of whether it was intentional. (Check out our blog on retention periods in Canada to learn more about how to remain compliant.)

Security.

But good information disposal doesn’t end once its retention period has ended. Even if you have permission to dispose of a file, doing so in an insecure way could come back to hurt you.

For example, keeping financial records in secure storage will be pointless in the long-run if you just throw them out as whole, readable documents when you’re finished with them. Nothing that contains banking info, social security numbers, personal addresses, or any other sensitive information should be readable when you get rid of it. (Learn more about compliant and secure disposal in our blog on disposal legislation in Canada.)

Diligence.

Finally, good disposal means frequent and intelligent disposal. Just because a record has passed its retention period does not always mean it should be disposed of right away; some records hold operational and archival value for many years after their immediate relevance has passed.

But not every record does. Holding onto important records because you know they still have value is responsible custodianship. Holding onto unimportant records you’re legally allowed to dispose of because you forgot about them or because you worry that they might have value is just wasting storage space. In small amounts, this is a small problem, but it’s best to stay ahead of it before it grows into a large one after years of neglect.

Disposition doesn’t just mean destroying records when you’re done with them, it can also mean moving them to long-term archival storage. Rather than simply holding onto everything in the same place for as long as possible, good custodianship means deliberate, prompt disposition decisions for each record at the end of its lifecycle. Consciously deciding what happens to your records and keeping track of these decisions is an extension of good custodianship. It will also save you storage space and make it easier to track down old archival records should you ever need them in the future.

Practicing Good Information Management

One simple way to assess and improve on your organization’s management of information is to think about how it handles each of these four stages, and how well it achieves each stages’ goals. Below is a set of questions we recommend asking yourself about each stage of your information management. Try writing out specific, concrete answers to each for best effect. We will be creating a downloadable version of this checklist and sending it out with one of our bi-weekly newsletters, so subscribe to make sure you don’t miss it.

Acquisition

- What options for sending physical or digital documents to your organization are available to people? To your partners? Your clients or customers? To strangers?

- Which existing avenues for contacting or sending information to your organization are used most frequently? Which ones are under-utilized? Which are the simplest or most direct?

- Are there any potential avenues for contacting your organization or sending information to it that have not yet been adopted? Which options seem most valuable/efficient?

- How easy would it be for a stranger to get in touch with your organization? What about getting in touch with specific members (i.e. sales staff, managers, etc.)?

- What comes up when you search for your business on Google? What information would be valuable to include that’s not there already?

- How much information does your organization collect per month on average?

- How many documents/files are generated within your organization per year?

- Where does each type of file go when it’s received or generated? Where is it first stored?

Custodianship

- How fast would you be able to retrieve any given file within your organization’s collection?

- How quickly or easily would a brand new member of your organization be able to find a specific file only using the indexing schema, without assistance?

- What would a bad actor from outside your organization have to do to get access to your sensitive files? What obstacles would they have to overcome?

- How many information security breaches has your organization had in the past?

- How likely is your information to be targeted by bad actors trying to steal or leak it?

- Do you have any old archives of records? When was the last time they were thoroughly re-evaluated or reorganized? How long would it take to do it again?

- How often is your indexing schema re-evaluated and updated? How well is your current indexing schema serving your larger operational goals and organizational strategy?

Distribution

- Would it be safe for every member of your organization to have access to every file in its possession?

- Which files (if any) should not be accessible to your entire organization? Who should they be accessible to? What precautions are in place to ensure that access to them is restricted?

- How satisfied are your organization’s staff with their ability to access information? Have there been any complaints from staff about access?

- Are there any operational delays which are attributable to information delivery? If so, how might these be remedied?

Disposal

- Does someone in your organization know the required retention periods for all of its records? Which records need to be kept indefinitely?

- If you have any old archives of records, how many have passed their retention periods? How many could you delete, destroy, or move to the archive to save space?

- How does your organization typically get rid of old paper records? How secure is your destruction solution?

- How does your organization get rid of old digital records? How secure and how total is that destruction solution?

- What does your organization do with records once they pass their retention period? Is there a formal policy in place?